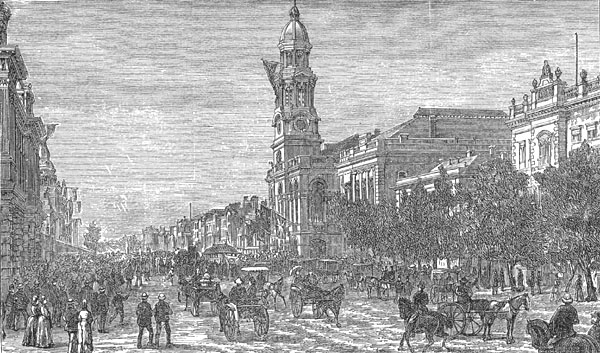

King William Street, Adelaide

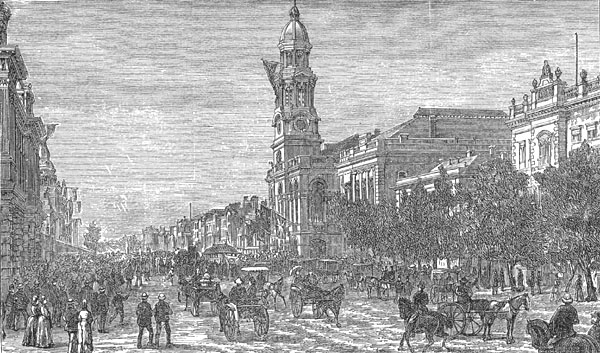

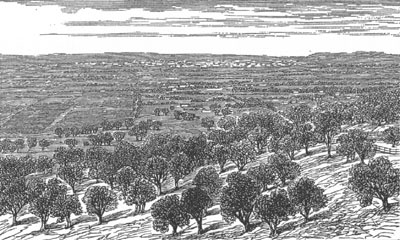

THE city of Adelaide is the capital of the colony of South Australia, and is in 31° 57' S. latitude, and 138° 38' E. longitude. It is picturesquely situated on a wide-spreading and fertile plain, which is bounded on the west by the Gulf of St. Vincent, and on the south and east by ranges of mountains, grassed and timbered to their summits, the highest point of which, Mount Lofty, is 2,300 feet above the level of the sea. The slopes of these mountains are studded with the residences of well-to-do people, and pretty villages, with gardens, vineyards, and orangeries, nestle in their glens, and at their base. The city stands on a small mountain stream, called the Torrens, which divides it into two parts, South and North Adelaide. The river is crossed by two or three handsome bridges, and its waters have been turned' into an ornamental lake, on which boating exercise is taken, and regattas are held. South Adelaide, or Adelaide, as it is usually called, is the city proper. It is about a mile square, and laid out into broad, rectangular streets. Looking towards the Park lands, by which the city is environed, are four terraces, called respectively North, South, East, and West. The most imposing is North Terrace, where are the Governor's Residence, the Public Library, the Museum, the University, the Exhibition Buildings, and the new Houses of Parliament. Many of the streets are substantial and well-built, notably Bundle, Grenfell, Pirie, Flinders, and King William Streets. The last named, of which we present a picture, is one of the finest streets in the Southern hemisphere. We must say, however, that the picture, which has evidently been taken on some occasion of public interest, probably the opening of the Town Hall, shown on the right, does not give by any means an adequate representation of what the street is now. Since it was taken a double line of tramways has been laid down, the sides of the street have been flagged and curbed, and telegraph lines have been stretched overhead on the right and left. The Post Office, the foundation stone of which was laid by the Duke of Edinburgh, a structure surmounted by a lofty clock-tower, and larger than the Town Hall, does not appear. The new buildings, which strike the eye of a visitor, are the Eagle Chambers, 'Advertiser' Offices, and the numerous Banks, the size and architecture of which indicate the faith of financial men in the stability and increasing prosperity of South Australia. These erections are mostly of fine white sandstone, which keeps for years fresh and clean in the almost smokeless atmosphere. The churches are so numerous and beautiful, that Adelaide has been called 'the city of churches.' The primary schools are well-built, and furnished with every needful appliance for efficient teaching. St. Peter's, Prince Alfred, and Whinham Colleges provide an excellent middle-class education for boys, and the Advanced School, a state High School, together with several private seminaries, does the same for girls. The University has a staff of able professors, and is doing a good work in equipping many for the learned professions. It has already sent forth a goodly number of both gentlemen and lady graduates. The city is ornamented by several squares, laid out with grass, flowers, and shrubs. 'But the glory of Adelaide,' says Mr. Harcus, 'and the pride of its citizens, is our beautiful Botanic Gardens, which, under the magic wand of Dr. Richard Schomburg, has grown into a thing of beauty which will be a joy for ever . . . . They who have seen all the Botanic Gardens in the other colonies, without a moment's doubt or hesitation give the palm to us. Dr. Schomburgh has the clear insight and creative power of a poet; and he has created a scene of beauty on which the eye can never feast itself sufficiently.'

|

Botanic Gardens, Adelaide |

The city is surrounded by Park lands, about a quarter of a mile in breadth, on which the citizens are permitted, for a small consideration, to depasture their cows, and where the young South Australians play in their leisure hours cricket and football. These free open spaces contribute largely to the health and pleasure of the inhabitants. Beyond these park lands are the suburbs of the city, Parkside, Norwood, Hindmarsh, and Thebarton, and other growing townships, with their municipal councils and mayors. North Adelaide is municipally part of the city, but it is really suburban. Built on rising ground, and commanding a fine view of the city and hills, it has become a favourite place of residence. The suburbs have far outgrown the city, for whilst the city alone has only 45,000 inhabitants, it has with the suburbs 110,000. Some of the townships, such as Kensington, Glen Osmond, and Mitcham, that have for their background the Mount Lofty range of hills, are pleasantly situated, affording a grand view of the waters of the Gulf. Here some of the most delightful private residences are to be found. 'Many of the suburban gardens,' in which these townships are embowered, 'are rich and beautiful, and vineyards and orangeries abound. When the fruit trees are in bloom or covered with ripening fruit, they present a scene of rare beauty, while the air is fragrant with the mingled odours of "Araby the blest."

Adelaide comes very far short of Melbourne and Sydney in commercial importance, but its trade and commerce have been of steady growth, and promise a greater development in the future. It has depended very largely upon the wheat harvests in the past, so as to earn for itself from the other colonial cities the somewhat contemptuous soubriquet of 'the farinaceous village.' But the extensive mineral resources of the colony, its varied fruits and its wool, all of which are coming more extensively into the market, will contribute yet more largely to the wealth of its metropolis. It has certain advantages, the full benefit of which it has not yet realised. From Adelaide starts the Intercolonial Railway, which opens communication with the other colonial capitals, Melbourne, Sydney, and Brisbane. Here the European mails are landed, and sent on to the other colonies. Through Adelaide stretches over the continent the overland telegraph line, the laying of which reflects so much credit on the enterprise of South Australia, and which by the submarine cable from Port Darwin connects the whole of Australasia with the outside world. From Adelaide the Overland Railway is being constructed, which, if the original project be carried out, will run from the south to the north of Australia, a distance of 1,850 miles, opening up a country rich in mineral and pastoral resources. Already between 600 and 700 miles of this line have been laid. If the distance which can be travelled from Adelaide by rail to Mount Gambier in the south-east be added to this, South Australia hag one continuous line of railway, approaching 1,000 miles in length, within her own territory, the like of which cannot be found in any other British possession, with the exception of Canada.

About eight miles from the city, on the Gulf of St. Vincent, is Port Adelaide, the principal port in the colony. Like some of the towns of Holland it has been literally built up out of the sea. Originally it was a swamp, or creek, over which the tide spread. But the creek has been confined within banks, converting it into a river. Millions of tons of silt, dredged from the river, have been piled on the swamp. Substantial wharves have been erected, and huge warehouses in which merchants carry on their business. There is now to be seen a forest of masts of vessels, from small launches up to ships of 3000 tons register, lying alongside the wharves. The principal exports are wheat, silver, copper, and wool. Six miles from the city in an almost opposite direction, situated also on the Gulf, is the beautiful watering-town of Glenelg. It is served from the city by two lines of railway. During the summer it is crowded with visitors, and in the evenings and on holidays, the hot and dusty citizens flock to it, by rail and traps, to get a breath of fresh air and a dip in the briny ocean. It is here that the colony was proclaimed in 1856. The old gum tree under which the proclamation was read is still to be seen. And on Commemoration Day, December 28th, from 60,000 to 80,000 South Australians gather annually to celebrate the event.

|

Adelaide Plains |

Adelaide has the reputation of being in summer the hottest of Australian cities. The thermometer often registers from 105° to 110° in the shade. When the hot winds, attended with dust storms, prevail, it is exceedingly unpleasant, and only a few human salamanders can sleep at nights. But this excessive heat generally only lasts two or three days, when a pleasant change takes place. Besides, the heat being free from moisture, it does not produce exhaustion, or injure the health, as 20° less heat in India would do. 'As the result of experience and observation,' says Mr. Harcus, 'I can say that even on the hottest day men can follow their ordinary employments without exhaustion.' For the rest of the year, eight months or so, the climate is delightful. We can testify from personal experience, to the perfect truthfulness of what may seem to Englishmen an exaggerated statement. On the days during the months when it does not rain, the climate is unsurpassingly beautiful; "the air is pure, soft, balmy, and cool — such as one might imagine would blow over the plains of heaven.' On such days mere existence is an enjoyment. It is very beneficial to people suffering from asthma, bronchial affections, and consumption. Invalids who have come to Adelaide, if they did not arrive too late, have had their days lengthened, and the lives of many have been ultimately saved, by the dry, pure, salubrious atmosphere; moreover the heat, which is sometimes so unpleasant to human beings, ripens the fruits of the earth, so necessary to health in a hot climate, making Adelaide and its neighbourhood one of the richest fruit-producing regions on the face of the earth. Here grapes, figs, peaches, nectarines, apricots, and oranges grow in the open air, without much culture. The ordinary English fruits also flourish abundantly, especially in the hill country around Adelaide. 'All these fruits, which are luxuries to the poor — and even to a large section of the middle class — in England, are, during the season, the daily food of the poorest in South Australia. When the fruits are ripe, there are but few tables on which several pounds of grapes or dozens of peaches and apricots are not found . . . . It would do the heart of an Englishman good to look upon the breakfast table of a South Australian of moderate means, groaning under the weight of the most luscious fruits.'

Primitive Methodism in South Australia will celebrate its Jubilee in Adelaide this year. The first Intercolonial Conference of our Australian districts will also meet there in October. We are fairly supplied with churches, and well represented by ministers, in Adelaide and its vicinity. Within the city area are Morphett-street church, with the Rev. J. G. Wright for minister, and Wellington-square, where the Rev. Hugh Gilmore exercises his ministry. Around the city are Parkside, Norwood, Port Adelaide and Prospect circuits, in each of which we have several chapels. The Book-Room, with Rev. J. H. Williams as steward, is in the centre of the city. Our position during the last ten years has been gradually strengthening, and would have been more rapid if we could have competed with other churches by placing our ministers regularly in the city and suburban churches. An improvement is however, taking place in this respect. We have ministers and laymen, loyal men and true, who are anxious to see our cause prosper, and never were its prospects brighter than they are now in the beautiful and growing capital of South Australia. J. W.

Source: The Primitive Methodist Magazine, Vol. XIII / LXXI, 1890