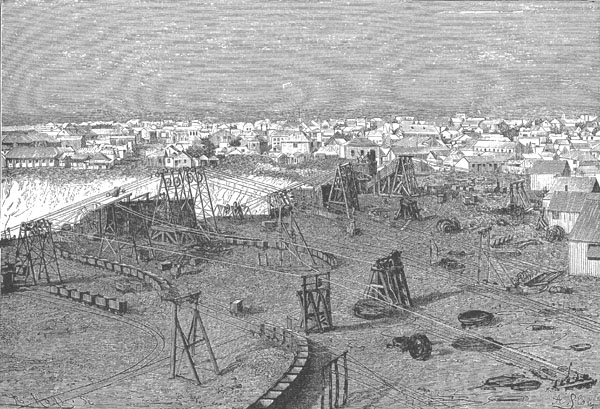

KIMBERLEY is the capital of the province of West Griqualand, which was annexed to Cape Colony in 1880. It is situated about the 29th degree S. Lat., and in the 25th meridian, E. It is the centre of the South African diamond region, which, though of immense wealth, is confined within a narrow area, lying between 28 and 30 degrees S. Lat., and the 24th and 26th meridians, E. Kimberley is a town of great wealth and importance. Its population fluctuates, but it may be roughly estimated at 25,000. It is about 650 miles from Cape Town, with which it is connected by rail, and about 450 miles from Port Elizabeth, with which, through the junction of the Western and Midland lines, it is also in railway communication. The journey takes thirty-six hours from Cape Town, and twenty-seven hours from Port Elizabeth. Like other colonial towns of similar origin, it has still many dwellings of canvas, wood, and iron, but these are being rapidly superseded by more solid buildings of brick and stone. It is well provided with banks, churches, public rooms, and hotels, some of which are fine buildings, betokening the confidence of those who have built them in the future stability and progress of the town.

Kimberley and its diamond mine

It owes its origin and wealth entirely to the discovery and working of the diamond mines. Where it now stands was formerly a desert, inhabited by Korannas, who dragged out a monotonous existence, finding there a scanty pasturage for their flocks. No one would have dreamt of its ever becoming a scene of busy industry. Under its barren surface the precious metals had lain hidden, until their accidental discovery quickly peopled its hitherto dreary solitudes with the rough pioneers of industry and commerce. In the year 1867 a trader obtained from a Boer in the Hopetown district a bright stone which his children were using as a plaything. This stone was sent to the Cape, where its true nature as a diamond was soon recognised, and subsequently forwarded to the Paris Exhibition, and sold for £500. This discovery led to researches in various places on or near to the Vaal river, where diamonds were obtained. Here, from Bloemhof in the Transvaal to the confluence of the Hartz and Vaal rivers, the oldest fields were situated. Within a year after the discovery of the crystal stone, the whole of South Africa from end to end was seized with the diamond fever. Young and old, masters and servants, people from the town and country, flocked to the fields. Dutch Boers who had called the first diamonds, contemptuously, 'shining pebbles,' trekked thither in whole families. Long rows of tenements sprang up as by magic; encampments became regular towns of 4,000 or 5,000 inhabitants. But when the report spread that on the plain of Dutoitspan Farm, below the river diggings on the Vaal, diamonds had been found in abundance on the surface of the earth, the old alluvial diggings were almost abandoned, and people hurried off to the 'dry diggings,' which were supposed to be richer. The intelligence that the 'Star of South Africa,' a diamond of eighty-three carats and a half, and which afterwards sold in the rough for £11,200, had been picked up, was no sooner spread abroad, than every European steamer was crowded with hundreds, on their way to the now famous diggings. In connection with the central diggings four mines were opened, Dutoits Pan and Bultfontein in the south-east, and Old De Beers and Kimberley, called at first New Rush, in the northwest. Kimberley has turned out to be the richest, yielding the greatest number of diamonds for the square yard, and of every quality. The town which it created has become the centre of the diamond industry, as well as the general trade of Griqualand West.

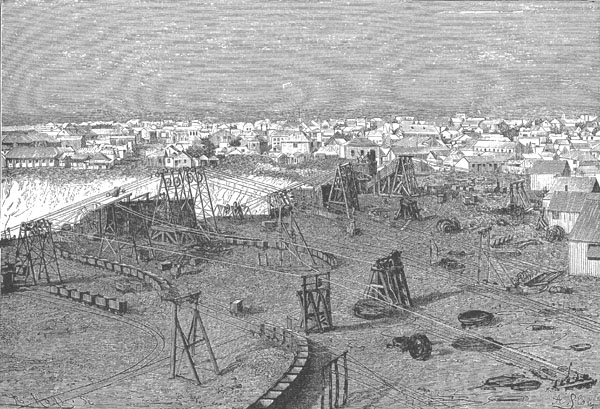

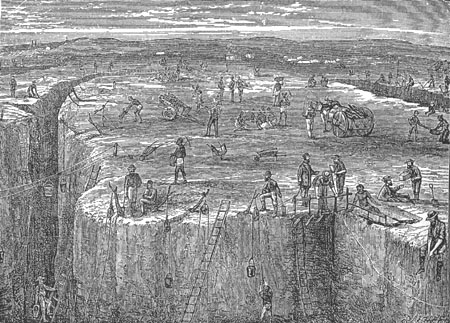

Diamond Mine, Kimberley

The Kimberley mine, which is shown in the foreground of the picture, is said to be the largest artificial hole in the world. It covers a surface of thirty acres, and has a depth of four hundred feet. It consists of a vertical "pipe" of a roughly oval section, filled with an agglomerate of presumably igneous rock, which contains the diamonds, and surrounded by a thick layer of horizontal shale, with a depth of some two hundred and seventy feet, and is succeeded by amygoidal dolerite of unknown depth. The shale is called by the miners 'reef,' and the dolerite 'tough rock.' The 'pipe' is supposed to be the funnel of an ancient volcano. When the tough rock was reached the working became more difficult and expensive. It is blasted with dynamite, and then the loosened fragments are hauled up in huge buckets by aerial tramways of steel wire rope. At first hand-tackle was used, then horse whims, but engines are now employed, mostly twenty nominal horse-power Roby engines. Viewed from the edge of the clay walls this huge excavation presents a peculiar appearance. 'It is' says Dr. Holub, 'like a huge crater, which previously to the excavations, was filled to the brink with volcanic eruption, composed of crumbling diamond-bearing earth, consisting mainly of decomposed tufa. The crater now stands full of rectangular "claims," dug to every variety of depth. Before us vast masses of earth, piled up like pillars, clustered like towers, or spread out like plateaus; sometimes they seem standing erect as walls, sometimes they descend in steps, and here they seem to range themselves in terraces. . . . But this vision of the city of the dead dissolves, as you look into a teeming ant hill; all is life and eagerness and bustle. The very eye grows confused at the labyrinth of wires stretching out like a giant cobweb over the space below, while the movements of the countless buckets making their transit backwards and forwards only add to the bewilderment. Meanwhile to the ear everything is equally trying; there is the hoarse creaking of the windlasses, there is the perpetual hum of the wires, there is the constant thud of the falling masses of earth, there is the unceasing splash of water from the pumps, these combined with the shouts and singing of the labourers, so affect the nerves of the spectator, that, deafened and giddy, he is glad to retire from the strange and striking scene.'

The wealth which the pit has yielded is enormous. From 1879 to 1886 there were produced in the entire region diamonds to the value of £40,000,000 sterling, more than the value of all the diamonds in the world previous to that date. But of this amount the Kimberley mine alone, since its discovery in 1871, until 1886, yielded diamonds to the value of £20,000,000. At the beginning it was rushed by hundreds of adventurers, but as the expenses of working increased the number of claim holders decreased. Private holdings have gradually combined into Joint Stock and Limited liability Companies. Its palmy days were in 1871 and 1872. Fortunes were quickly made, but by many of the diggers just as quickly squandered. It is said that men in bravado could light their pipes with £5 notes. It became a den of drunkenness and all kinds of vice. High prices were paid for the necessaries of life, and water, at certain seasons of the year, could scarcely be obtained. Half-a-crown a bucket was often paid for water for domestic purposes. But gradually the town settled into more regular ways. The wild and reckless part of the population moved off to other places, and were replaced by men who pursued diamond digging as a systematic industry. Regular streets were formed, and substantial buildings erected. Sanitary improvements were made, and water was conducted, at great expense, from the Vaal river and distributed through the town. The greatest boon has been the opening of railway communication with the Cape towns. When the only means for the transit of merchandise was the slow ox-waggon, every necessary of life could be obtained only at a great cost. But in 1885 the Western line was opened. Since then the Midland has been connected with it by a line from Newport to De Aar, so that there is now direct communication with Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. It is in contemplation to link the Eastern line with these also. When this is accomplished, the whole of the great trunk lines, the original objective of which was Kimberley, will find their terminus there. The results of this railway communication have been to increase, by lessening the expenses, the dividends of the mining companies and the consumption of coal. Wood had become so dear that it was cheaper to burn coal at £15 and £20 per ton than to use it. Now good English coal can be obtained at £7 per ton.

The importance of Kimberley to the whole of Cape Colony cannot be over-estimated, its prosperity depending materially upon the state of the mining operations there. It has not inaptly been called the stomach of the country, any organic or functional derangement of which is sure to affect the whole system. Many can remember how little business was done in the Eastern Province before the mines were opened, and what an impulse was given to the trade of the country by their working. Towns sprang up on the route to them, and old towns increased in population and wealth. The serious depression through which the Cape passed a few years ago was caused mainly by the partial collapse of the mining industry. At that time the writer received a letter from a friend there which described in a graphic manner the causes of the collapse. 'When the mines got too deep to be worked by "diggers," the holdings were amalgamated into companies. The companies set to work on a magnificent scale, spent fortunes in machinery and appliances, and poured millions of carats of diamonds into the market. The immediate result was that diamonds declined in value, and the companies have, with few exceptions, proved complete failures. Most of them paid no dividends, many are in liquidation, or have suspended operations. Hands have been discharged by hundreds. Night, in fact, has followed day. This is not an exhaustive summary of the causes of our unhappy plight. The I.D.B. (illicit diamond buying) has much to account for; and the community itself for its reckless extravagance and utter want of foresight.' Kimberley has since recovered from the low-water mark of 1883. It was evident to the thoughtful observer that it was then passing through a transition period. As a place of wealth and importance it would not cease to exist, but only as a place for wild and demoralising speculation, for the rapid making and losing of fortunes. The probability was that it would become even more a centre of trade for the natives and European settlers, in the Northern Transvaal and Bechuanaland. This hope is, we believe, in process of fulfilment. It is adapting itself to a new order of things, and its concentrated wealth is seeking for itself outlets in ways of business less immediately lucrative, but more stable than the diamond operations of the past. The dark season through which it passed will be seen to have worked good both for Kimberley itself and the whole of South Africa. As to the diamond mines, they are likely to yield a steady stream of wealth for many years to come. How long their resources will hold out it is impossible to say. But scientific men suppose that they are likely to yield £2,000,000 per year for at least fifty years to come. In the meantime Kimberley, connected with the Zambezi by rail, will have become the depot of immense regions which will have been opened to industry and civilisation.

Ample provision is made for the religious wants of both Europeans and natives. The most of the churches are represented. Were there an opening for Primitive Methodism, it would be an advantage to us to have a centre of operations at Kimberley. It is on the high road to the Zambezi regions. It is nearer by two hundred miles to our new missions, and on a more direct line from Cape Town, than Aliwal North. Probably with its increasing development such an opening may present itself. If we aspire to do a great work for South-Central Africa it would be wise to occupy and hold such a position on the way as Kimberley offers. At any rate it must be to us as a people a place of interest as the last European town in South Africa at which our missionaries can make preparations for entering the still dark regions beyond. J. W.

Source: The Primitive Methodist Magazine, Vol. XIII / LXXI, 1890